by Judy Bentley

Delridge, a neighborhood of dells and ridges, began as a gritty steel town. In 1905, William Pigott and Judge E.M. Wilson opened the Seattle Steel Company to great acclaim. Seattle movers and shakers hyped the beginning of a new industrial epoch, and a special train carried 500 of Seattle’s leading citizens out to the mill for an opening reception. The steel mill has been operating ever since, under various names and ownership, gradually filling in the tideflats on a cove at the northeastern end of the Duwamish Peninsula.

Delridge, a new name, encompasses Duwamish village sites, the settlement of Humphry, and the older neighborhoods of Youngstown and Pigeon Point. The ridge to the east is Puget Ridge, with Pigeon Point at its northern end. To the west is the ridge that rises to Duwamish Head and traditionally separated Delridge from West Seattle along Avalon Way and 35th. The watersheds of Puget Creek and Longfellow Creek create the dells.

For two thousand years, the Duwamish had several winter villages and seasonal camps lining the water. They built longhouses for the winter and wove mats attached to a pole frame for the camps. They constructed sweat lodges, fish weirs and aerial duck nets and gathered a bounty of seafood from the river, bay, and tideflats. In the early 1850’s, when Euro-American settlers arrived, some 300 Duwamish were camped at the mouth of the river. Their numbers had already been reduced by diseases that had arrived even before the settlers. After the treaties of 1853 and 1854, many moved across the Sound to the Suquamish Reservation, and some went to the Tulalip or Yakima reservations; others stayed near the waterfront. During a land development boom in 1893, several Duwamish were burned out of their homes on the peninsula. From then on, there were no permanent Duwamish sites. By the 1910 and 1920 censuses, Native Americans formed only 1% of the population of the northeastern Duwamish peninsula.

The land development that crowded out the Duwamish rippled through the tideflats and Young’s Cove. In the late 1800’s, John Longfellow had farmed this cove and logged the hills and valley for a cash crop. The trout creek the Duwamish called to-AH-wee was renamed Longfellow Creek. Land developers established the small settlement of Humphry where trees had been cut. Puget Mill Company opened much of the land.

Humphry grew up to a steel town when Pigott bought land for the Northern Pacific Railroad and 55 acres for himself on the tidelands, an ideal site near the waterfront and the proposed rail line from downtown to West Seattle. When the mill opened, Humphry was renamed Youngstown, for the steel town in Ohio. The company offered jobs to 140 employees, including 70 skilled ironworkers. Workers came from everywhere—Tacoma, Portland, St. Louis, England, Italy–to work at the mill and live in rooming houses or homes the company provided or homes they built themselves.

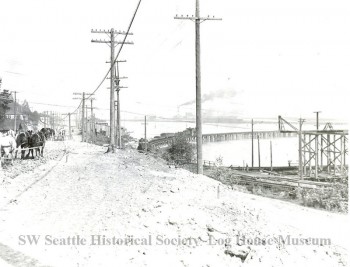

The streetcar line from Seattle crossed the Duwamish River on a trestle, turned and came south at Pigeon Point. At Andover and 24th Ave., where the tideflats ended, neighborhood businesses opened—a meat market, a grocery store, a tavern, a pool hall, and soon a Congregational Church and a Salvation Army hall. European immigrants from many countries arrived, with Scandinavians concentrated on Pigeon Point and Italians in the “gulch. E/p>

As families moved in, Youngstown needed a school for the workers Echildren. In 1906 the steel mill provided a room in a tiny office building, and 70 children showed up the first day. Once Youngstown was annexed to West Seattle and then to Seattle, a move tavern owners and the steel mill opposed, the Seattle School District built a wooden school for Youngstown with five classrooms. The school on 24th Avenue (now Delridge Way) was replaced by brick in 1917 with an addition in 1929. For 80 years, Youngstown/Cooper School provided education for the children of immigrants and a heart for the neighborhood. Today a new Cooper School at the top of Puget Ridge and Sanislo Elementary continue to serve Delridge children, as well as others.

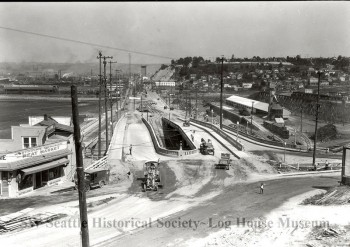

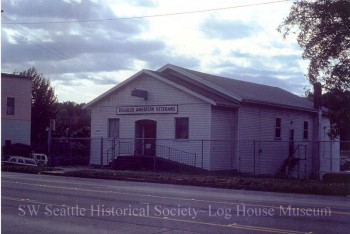

Delridge was a working-class neighborhood, a contrast to the middle-class neighborhood of West Seattle on the hill to the west. In the 1930’s aspiring parents successfully petitioned the school board to change the name of the school from Youngstown, with its steel city connotations, to the Frank B. Cooper School, after a progressive Seattle superintendent. Residents also raised money, bought land, and built the Youngstown Improvement Club as a social gathering place. They persuaded the city to pave 24th Avenue and rename it Delridge Way. The city developed the Delridge Playfield and community center, and the West Seattle Golf Course grew on land that leads up the ridge to Camp Long.

The steel mill continued to dominate the neighborhood, but residents diversified, finding work in fishing, canneries, flour mills, Boeing, and other Seattle employers. Over the years, the tideflats were filled, and the port grew on the north side of Spokane Street, once considered a highway.

During World War II, the few Japanese-American families in Delridge went to internment camps, and temporary war-worker housing crowded the playfields and empty lots. An influx of workers from the Midwest and South changed the neighborhood’s demographics. By 1990, Filipinos, Koreans, Samoans, and African-Americans made up more than one-third of the population; the high incidence of home ownership during the 1950s declined and the number of renters increased.

South Seattle Community College opened on the top of Puget Ridge in 1969. Traffic increased; larger businesses and office buildings crowded out neighborhood businesses. But over the years, the greenness of Delridge—its potential for landslides, periodic flooding, its ravines and creeks saved it from rapid development.

A ten-year effort, led by Seattle Public Utilities and Parks and Recreation, restored Longfellow Creek to health and blazed a heritage trail from Yancey Street south of the steel mill to a bog at Roxhill. In recent years, Delridge Neighborhoods Development Association has converted the old Cooper School to the Youngstown Cultural Arts Center, funded low-income housing, and envisioned a new Delridge Library integrated with housing and street-front space for small businesses and offices.

Throughout the years, Delridge has maintained its reputation as a boot strap community. Alumni of the school talk proudly and fondly of having grown up here. “Everybody was brought up by their bootstraps and I think a great deal of it was schools like Youngstown, Erecalls Dale Corliss, eighth grade class of 1938.

Comments are closed.